How many Ebola cases are there really?

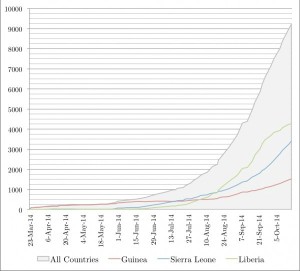

Every couple of days, the World Health Organization (WHO) issues a “situation update” on the Ebola epidemic, with new numbers of cases and deaths for each of the affected countries. These numbers―9216 and 4555 respectively, according to Friday’s update―are instantly reported and tweeted around the world. They’re also quickly translated into ever-more frightening graphics by people who follow the epidemic closely, such as virologist Ian Mackay of the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia, and Maia Majumder, a Ph.D. student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge who visualizes the data on her website and publishes projections on HealthMap, an online information system for outbreaks.

But it’s widely known that the real situation is much worse than the numbers show because many cases don’t make it into the official statistics. Underreporting occurs in every disease outbreak anywhere, but keeping track of Ebola in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone has been particularly difficult. And the epidemic unfolds, underreporting appears to be getting worse. (“It’s a mess,” Mackay says.)

But it’s widely known that the real situation is much worse than the numbers show because many cases don’t make it into the official statistics. Underreporting occurs in every disease outbreak anywhere, but keeping track of Ebola in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone has been particularly difficult. And the epidemic unfolds, underreporting appears to be getting worse. (“It’s a mess,” Mackay says.)

So what do the WHO numbers really mean—and how can researchers estimate the actual number of victims? Here are answers to some key questions.

Does WHO acknowledge that the numbers are too low?

Absolutely. In August, it said that the reported numbers “vastly underestimate” the epidemic’s magnitude. WHO’s situation updates frequently point out gaps in the data. The 8 October update, for instance, noted that there had been a fall in cases in Liberia the previous 3 weeks, but this was “unlikely to be genuine,” the report said. “Rather, it reflects a deterioration in the ability of overwhelmed responders to record accurate epidemiological data. It is clear from field reports and first responders that [Ebola] cases are being under-reported from several key locations, and laboratory data that have not yet been integrated into official estimates indicate an increase in the number of new cases in Liberia.”

Where do the reported numbers come from, and why are they always too low?

Officially, the governments of Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia transmit the numbers to WHO, which then passes them on to the world. But WHO is also closely involved in helping determine the numbers. The data come from several sources, says WHO epidemiologist Christopher Dye; the three main ones are clinics and treatment centers, laboratories doing Ebola tests, and burial teams.

Getting the numbers right is hard for many reasons. Many patients don’t seek medical care, for instance, because they don’t trust the medical system or because they live too far away. Of those who do, some die along the way, and some are turned away because treatment centers are overloaded. Of Ebola people who die at home, some are buried without ever coming to officials’ attention. It can also take time for recorded information to be passed on and entered into data reporting systems.

Testing is a big problem as well. The reports break down the numbers into suspected cases, based mostly on symptoms; probable cases, in which someone had symptoms and a link to a known Ebola case; and confirmed cases, in which a patient sample tested positive in the lab. In an ideal world, all suspected and probable cases would eventually be tested, but testing capacity is lacking. In WHO’s 15 October report, only 56% of the cases in the three countries was confirmed; in Liberia, where testing is huge problem, it was just 22%. (Friday’s report did not break down Liberia’s cases and said the data were “temporarily unavailable.”)

Dye says WHO and other groups are trying hard to improve the reporting on the ground. Among other things, they are trying to set up a system that would provide every patient with a unique identification number. Now, Dye says, patients who enter an Ebola clinic and then have a sample tested in the lab may enter the reports twice, because there is no way to know that the lab and the clinic were recording the same patient.

Are there ways to estimate the extent of the underreporting?

There are. For instance, In a technique called capture-recapture, epidemiologists visit one area or district and determine what percentage of the Ebola cases and deaths there has found its way into official records. “You throw out the net twice, and you compare,” says Martin Meltzer of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta, who is modeling the Ebola epidemic. (The term capture-recapture was borrowed from researchers who study the size of wildlife populations using two rounds of trapping.) But this method is logistically challenging and possibly dangerous, given the hostilities that some Ebola response teams have met, Meltzer says: “I’m not going to ask people to risk their lives to collect some data.”

For a paper published last month, Meltzer and his colleagues used a different technique. CDC has a computer model that, among other things, calculates how many hospital beds should be in use at any given time based on the cumulative number of cases at that moment. For 28 August, the time the paper was written, that number was 143 beds for Liberia; but people in the field told Meltzer that the actual number of beds in use was 320, a factor of 2.24 higher. (These numbers can be found in an annex to the paper.) “We had heard some other numbers that were higher, so we rounded that up to a correction factor of 2.5,” Meltzer says. But it’s a very rough approximation. Also, underreporting is likely to vary greatly from one place to another and over time, he says.

The CDC team’s widely reported worst case projection of 1.4 million cases by 20 January was based on the correction factor of 2.5, and assuming control efforts didn’t improve. It included only Liberia and Sierra Leone; in Guinea, the reported numbers of cases have fluctuated too much to make a reasonable projection, Meltzer says, which could also could be partly due to underreporting.