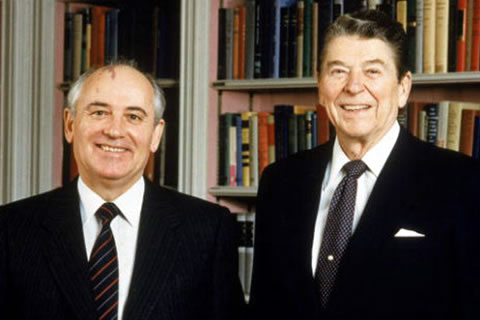

Did the Cold War End So that the War on Terror Could Begin?

Many of us regarded the mysterious transition with skepticism. Why would communism, which had slain some 100 million people1 during is ruthless conquest of half the planet, suddenly don a smiley-face, introduce freedoms, and abandon its sworn goal of world domination?